would be easily translated for

(e)would capture not only pain severity, but also the perception of how pain interfered with daily life.

Test Construction Standards

As a guide to scale construction, we used

Measurement Conceptualization: Multiple Dimensions of Pain

That pain is multidimensional was made clear during our patient interviews: patients reported that an adequate representation of pain required more than one simple measure of pain intensity.

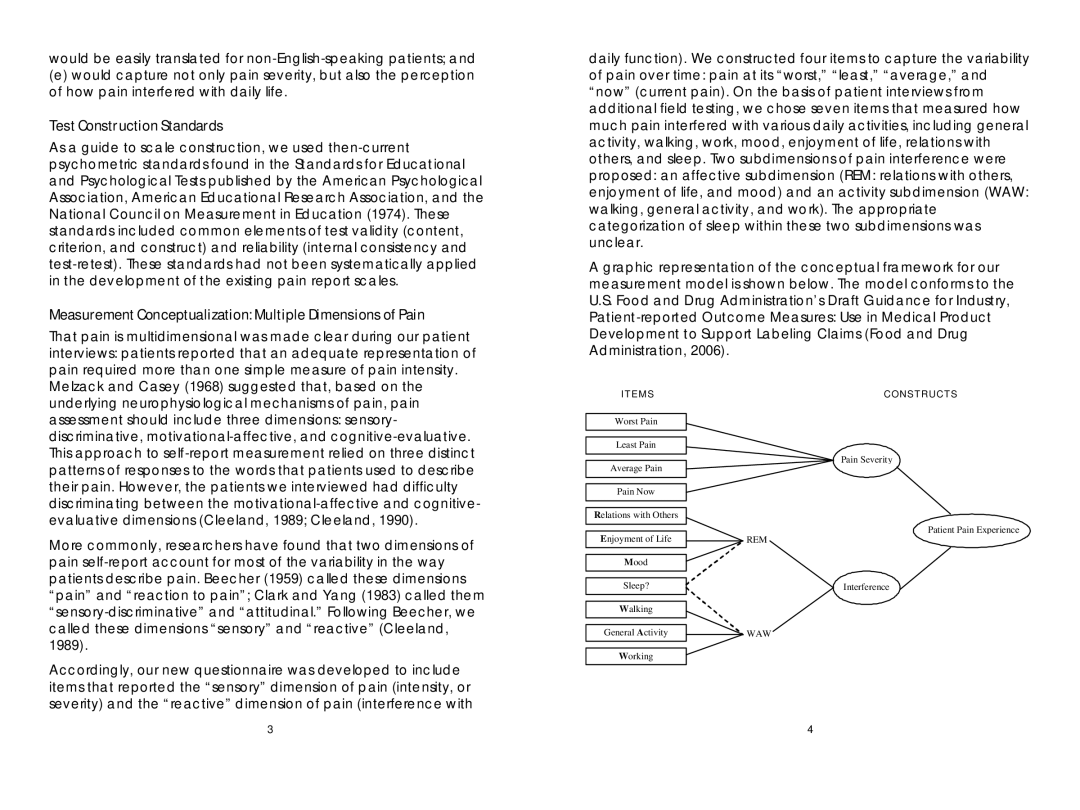

daily function). We constructed four items to capture the variability of pain over time: pain at its “worst,”“least,”“average,”and “now”(current pain). On the basis of patient interviews from additional field testing, we chose seven items that measured how much pain interfered with various daily activities, including general activity, walking, work, mood, enjoyment of life, relations with others, and sleep. Two subdimensions of pain interference were proposed: an affective subdimension (REM: relations with others, enjoyment of life, and mood) and an activity subdimension (WAW: walking, general activity, and work). The appropriate categorization of sleep within these two subdimensions was unclear.

A graphic representation of the conceptual framework for our measurement model is shown below. The model conforms to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’ Draft Guidance for Industry,

Melzack and Casey (1968) suggested that, based on the underlying neurophysiological mechanisms of pain, pain assessment should include three dimensions: sensory- discriminative,

More commonly, researchers have found that two dimensions of pain

ITEMS

Worst Pain

Least Pain

Average Pain

Pain Now

Relations with Others

Enjoyment of Life

Mood

Sleep?

Walking

General Activity

CONSTRUCTS

Pain Severity

Patient Pain Experience

REM

Interference

WAW

Accordingly, our new questionnaire was developed to include items that reported the “sensory”dimension of pain (intensity, or severity) and the “reactive”dimension of pain (interference with

Working

3 | 4 |