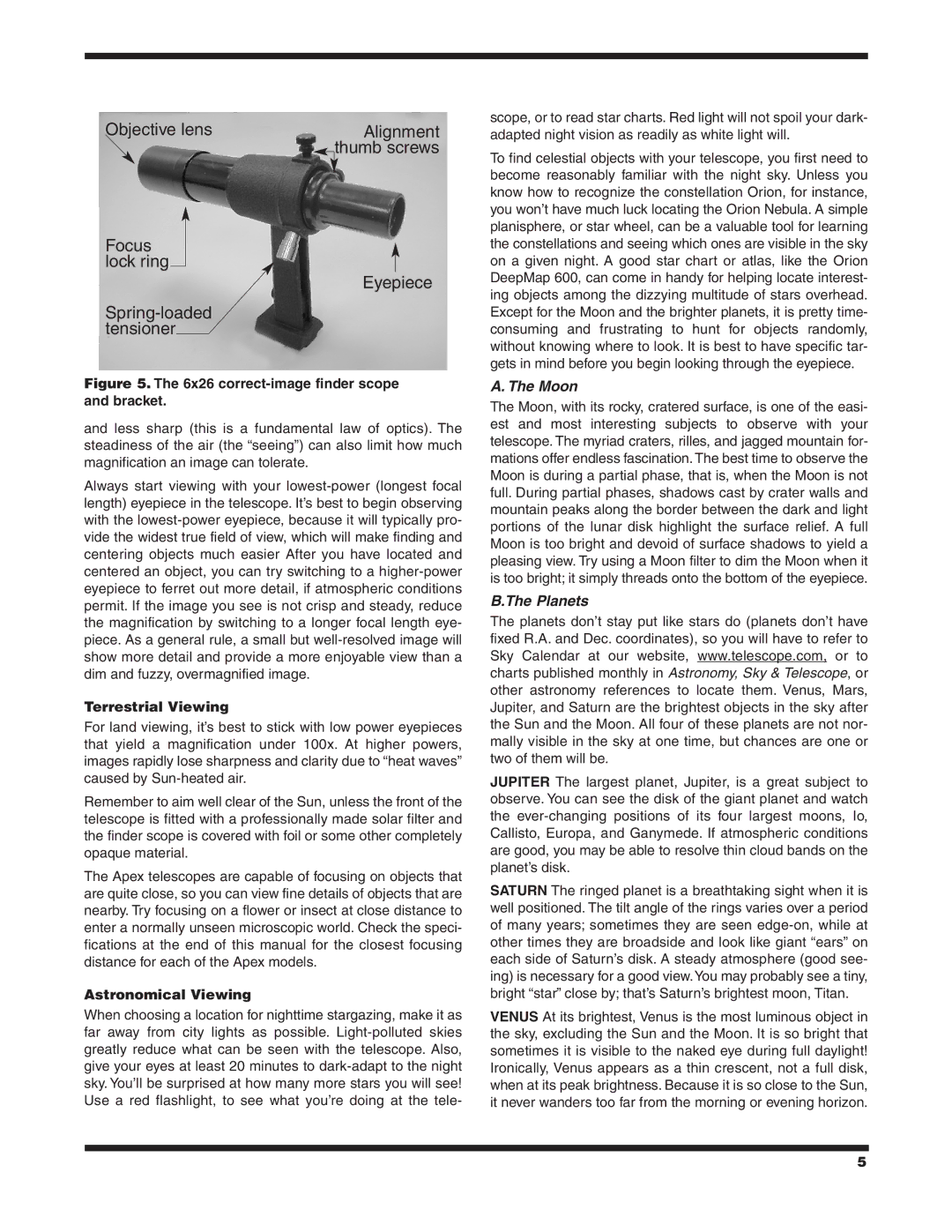

Objective lens | Alignment |

| thumb screws |

Focus

lock ring

Eyepiece

Eyepiece

Spring-loaded tensioner

Figure 5. The 6x26 correct-image finder scope and bracket.

and less sharp (this is a fundamental law of optics). The steadiness of the air (the “seeing”) can also limit how much magnification an image can tolerate.

Always start viewing with your lowest-power (longest focal length) eyepiece in the telescope. It’s best to begin observing with the lowest-power eyepiece, because it will typically pro- vide the widest true field of view, which will make finding and centering objects much easier After you have located and centered an object, you can try switching to a higher-power eyepiece to ferret out more detail, if atmospheric conditions permit. If the image you see is not crisp and steady, reduce the magnification by switching to a longer focal length eye- piece. As a general rule, a small but well-resolved image will show more detail and provide a more enjoyable view than a dim and fuzzy, overmagnified image.

Terrestrial Viewing

For land viewing, it’s best to stick with low power eyepieces that yield a magnification under 100x. At higher powers, images rapidly lose sharpness and clarity due to “heat waves” caused by Sun-heated air.

Remember to aim well clear of the Sun, unless the front of the telescope is fitted with a professionally made solar filter and the finder scope is covered with foil or some other completely opaque material.

The Apex telescopes are capable of focusing on objects that are quite close, so you can view fine details of objects that are nearby. Try focusing on a flower or insect at close distance to enter a normally unseen microscopic world. Check the speci- fications at the end of this manual for the closest focusing distance for each of the Apex models.

Astronomical Viewing

When choosing a location for nighttime stargazing, make it as far away from city lights as possible. Light-polluted skies greatly reduce what can be seen with the telescope. Also, give your eyes at least 20 minutes to dark-adapt to the night sky. You’ll be surprised at how many more stars you will see! Use a red flashlight, to see what you’re doing at the tele-

scope, or to read star charts. Red light will not spoil your dark- adapted night vision as readily as white light will.

To find celestial objects with your telescope, you first need to become reasonably familiar with the night sky. Unless you know how to recognize the constellation Orion, for instance, you won’t have much luck locating the Orion Nebula. A simple planisphere, or star wheel, can be a valuable tool for learning the constellations and seeing which ones are visible in the sky on a given night. A good star chart or atlas, like the Orion DeepMap 600, can come in handy for helping locate interest- ing objects among the dizzying multitude of stars overhead. Except for the Moon and the brighter planets, it is pretty time- consuming and frustrating to hunt for objects randomly, without knowing where to look. It is best to have specific tar- gets in mind before you begin looking through the eyepiece.

A. The Moon

The Moon, with its rocky, cratered surface, is one of the easi- est and most interesting subjects to observe with your telescope. The myriad craters, rilles, and jagged mountain for- mations offer endless fascination. The best time to observe the Moon is during a partial phase, that is, when the Moon is not full. During partial phases, shadows cast by crater walls and mountain peaks along the border between the dark and light portions of the lunar disk highlight the surface relief. A full Moon is too bright and devoid of surface shadows to yield a pleasing view. Try using a Moon filter to dim the Moon when it is too bright; it simply threads onto the bottom of the eyepiece.

B.The Planets

The planets don’t stay put like stars do (planets don’t have fixed R.A. and Dec. coordinates), so you will have to refer to Sky Calendar at our website, www.telescope.com, or to charts published monthly in Astronomy, Sky & Telescope, or other astronomy references to locate them. Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn are the brightest objects in the sky after the Sun and the Moon. All four of these planets are not nor- mally visible in the sky at one time, but chances are one or two of them will be.

JUPITER The largest planet, Jupiter, is a great subject to observe. You can see the disk of the giant planet and watch the ever-changing positions of its four largest moons, Io, Callisto, Europa, and Ganymede. If atmospheric conditions are good, you may be able to resolve thin cloud bands on the planet’s disk.

SATURN The ringed planet is a breathtaking sight when it is well positioned. The tilt angle of the rings varies over a period of many years; sometimes they are seen edge-on, while at other times they are broadside and look like giant “ears” on each side of Saturn’s disk. A steady atmosphere (good see- ing) is necessary for a good view.You may probably see a tiny, bright “star” close by; that’s Saturn’s brightest moon, Titan.

VENUS At its brightest, Venus is the most luminous object in the sky, excluding the Sun and the Moon. It is so bright that sometimes it is visible to the naked eye during full daylight! Ironically, Venus appears as a thin crescent, not a full disk, when at its peak brightness. Because it is so close to the Sun, it never wanders too far from the morning or evening horizon.