Watching the skies It’s a cool, crisp, early October morning and 100 people are standing together with their eyes fixed on the sky. “Peregrine Falcon over the bunker” shouts one of them as he simul- taneously records the event on a

8 / 9

By sunset, the herald with the tally counter called out the name “Peregrine Falcon” 256 more times, and recorded the passing of another four thousand hawks, eagles and falcons during their southward transit over historic Cape May, New Jersey.

Standing on the spacious hawk watch platform in Cape May Point State Park today, it’s difficult to imagine the Cape May Hawk Watch of thirty years ago.

Most noticeable, the crowds of birders were considerably smaller. Dozens during the week (perhaps) and scores on the weekends are nothing compared to the tens of thousands of people who now travel to Cape May each fall. In 1976, a rickety table that accommodated one person, is now a

200 visitors. Back then, a single person did everything – bird counting, back yard ornithology, and Cape May Bird Obser- vatory ambassador. Now, two official counters and two interpretive naturalists handle the flow of migrating hawks and questions from throngs of visiting hawk watchers.

at the forefront of environmental educa- tion, conservation and research for over 100 years. Initially, the Society was formed to combat wholesale market hunting of birds and to fight against the decimation of birds to supply feathers to the millinery industry. Our efforts, and those of other Audubon societies, were instrumental in the passage of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in 1911, a regulation that still protects nearly all bird species occurring in the United States today.

The Cape May Bird Observatory, one of New Jersey Audubon Society’s ten staffed centers, made its debut the same year that the Cape May Hawk Watch began. Thirty years later it is a world renowned

through Delaware Bay, which is a hemispherically important staging area for several species en route to the Arctic, breeding grassland birds, evaluating the impact of wind power development, and assessing population trends in migrating raptors and waterbirds.

But what makes Cape May so special when it comes to birds, especially those species that make annual migratory journeys. The business world mantra “location, location, location,” applies here. While migration occurs all over the Northern (and much of the southern) Hemisphere, it is not evenly apportioned. If you look at southern New Jersey, trapped between Delaware Bay to the west and the Atlantic Ocean to the east,

the peninsula where they back up before deciding to cross Delaware Bay. This often results in spectacular hawk flights and fallouts of migrants – much to the pleasure of birdwatchers.

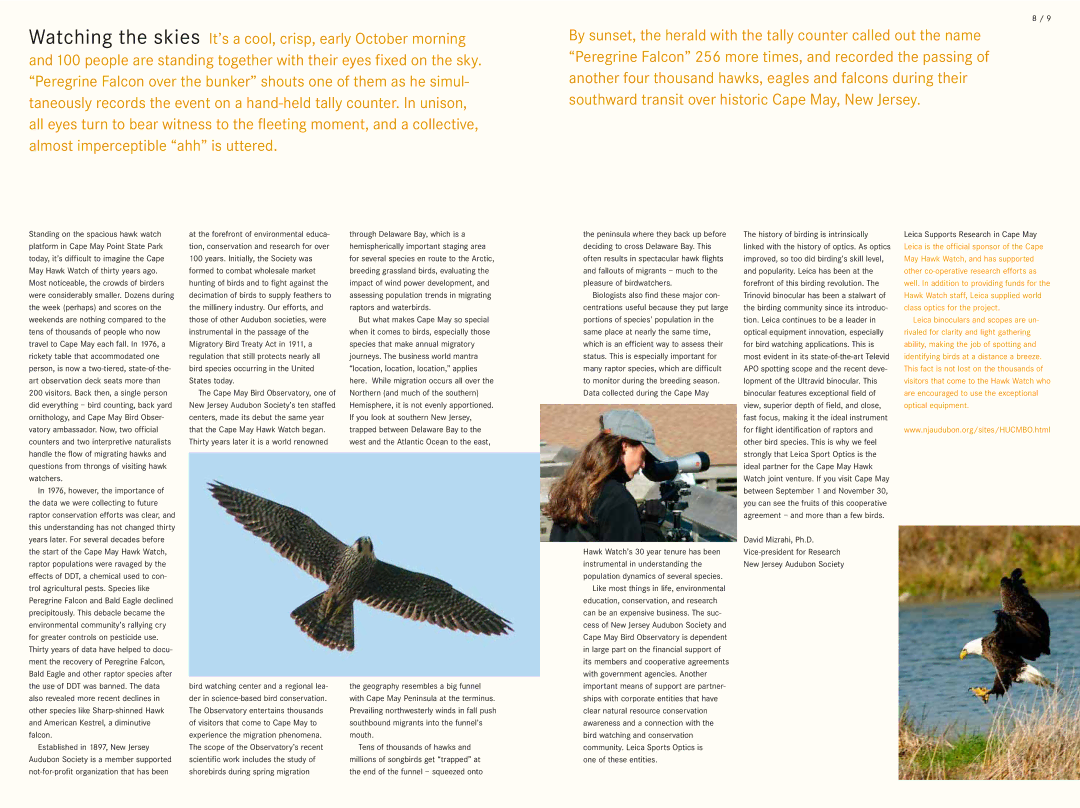

Biologists also find these major con- centrations useful because they put large portions of species’ population in the same place at nearly the same time, which is an efficient way to assess their status. This is especially important for many raptor species, which are difficult to monitor during the breeding season. Data collected during the Cape May

The history of birding is intrinsically linked with the history of optics. As optics improved, so too did birding’s skill level, and popularity. Leica has been at the forefront of this birding revolution. The Trinovid binocular has been a stalwart of the birding community since its introduc- tion. Leica continues to be a leader in optical equipment innovation, especially for bird watching applications. This is most evident in its

Leica Supports Research in Cape May Leica is the official sponsor of the Cape May Hawk Watch, and has supported other

Leica binoculars and scopes are un- rivaled for clarity and light gathering ability, making the job of spotting and identifying birds at a distance a breeze. This fact is not lost on the thousands of visitors that come to the Hawk Watch who are encouraged to use the exceptional optical equipment.

www.njaudubon.org/sites/HUCMBO.html

In 1976, however, the importance of the data we were collecting to future raptor conservation efforts was clear, and this understanding has not changed thirty years later. For several decades before the start of the Cape May Hawk Watch, raptor populations were ravaged by the effects of DDT, a chemical used to con- trol agricultural pests. Species like Peregrine Falcon and Bald Eagle declined precipitously. This debacle became the environmental community’s rallying cry for greater controls on pesticide use. Thirty years of data have helped to docu- ment the recovery of Peregrine Falcon, Bald Eagle and other raptor species after the use of DDT was banned. The data also revealed more recent declines in other species like

Established in 1897, New Jersey Audubon Society is a member supported

bird watching center and a regional lea- der in

the geography resembles a big funnel with Cape May Peninsula at the terminus. Prevailing northwesterly winds in fall push southbound migrants into the funnel’s mouth.

Tens of thousands of hawks and

millions of songbirds get “trapped” at the end of the funnel – squeezed onto

Hawk Watch’s 30 year tenure has been instrumental in understanding the population dynamics of several species.

Like most things in life, environmental education, conservation, and research can be an expensive business. The suc- cess of New Jersey Audubon Society and Cape May Bird Observatory is dependent in large part on the financial support of its members and cooperative agreements with government agencies. Another important means of support are partner- ships with corporate entities that have clear natural resource conservation awareness and a connection with the bird watching and conservation community. Leica Sports Optics is

one of these entities.

between September 1 and November 30, you can see the fruits of this cooperative agreement – and more than a few birds.

David Mizrahi, Ph.D.

New Jersey Audubon Society