"The Passive Parametric"

For years, we had been getting requests for a Manley parametric equalizer, but it looked daunting because every parametric we knew of used many op-amps and a "conventional parametric" would be very impractical to do with tubes. Not impossible, but it might take upwards of a dozen tubes per channel. A hybrid design using chips for cheapness and tubes for THD was almost opposite of how Manley Labs approaches professional audio gear and tube designs. Could we combine the best aspects of Pultecs, old console EQs and high end dedicated parametric EQs?

What is the definition of a "Parametric Equalizer"? We asked the man who invented the first Parametric Equalizer and coined the term. He shrugged his shoulders and indicated there really is no definition and it has become just a common description for all sorts of EQs. He presented a paper to the AES in 1971 when he was 19. His name is George Massenburg and still manufactures some of the best parametric EQs (GML) and still uses them daily for all of his major recordings. Maybe he originally meant "an EQ where one could adjust the level, frequency and Q independently". He probably also meant continuously variable controls (as was the fashion) but this was the first aspect to be "modified" when mastering engineers needed reset-ability and rotary switches. The next development was the variation of "Constant Bandwidth" as opposed to "Constant Q" in the original circuits. "Constant Q" implies the Q or bell shape stays the same at every setting of boost and cut. "Constant Bandwidth" implies the Q gets wider near flat and narrower as you boost or cut more. Pultecs and passive EQs were of the constant bandwidth type and most console EQs and digital EQs today are the constant bandwidth type because most of us prefer "musical" over "surgical". Lately we have seen the word "parametric" used for EQs without even a Q control.

We can call the Massive Passive a "passive parametric" but .... it

differs from George's concepts in a significant way. And this is important to understand, to best use the Massive Passive. The dB and bandwidth knobs are not independent. We already noted that the Q of the bell curve widens when the dB control is closer to flat. More significantly, the boost or cut depth varies with the bandwidth control. At the narrowest bandwidths (clockwise) you can dial in 20 dB of boost or cut. At the widest bandwidths you can only boost or cut 6 dB (and only 2 dB in the two 22-1K bands). Somehow, this still sounds musical and natural. The reason seems to be, simply using basic parts in a natural way without forcing them to behave in some idealized conceptual framework.

Another important concept. When you use the shelf curves the frequencies on the panel may or may nor correspond to other EQ's frequency markings. It seems there are accepted standards for filters and bell curves for specifying frequency, but not shelves. We use a common form of spec where the "freq" corresponds to the half-way dB point. So, if you have a shelf boost of 20 db set at 100 Hz, then at 100, it is boosting 10 dB. The full 20 dB of boost is happening until below 30 Hz. Not only that, like every other shelf EQ there will be a few dB of boost as high as 500 Hz or 1K. This is all normal, except.........

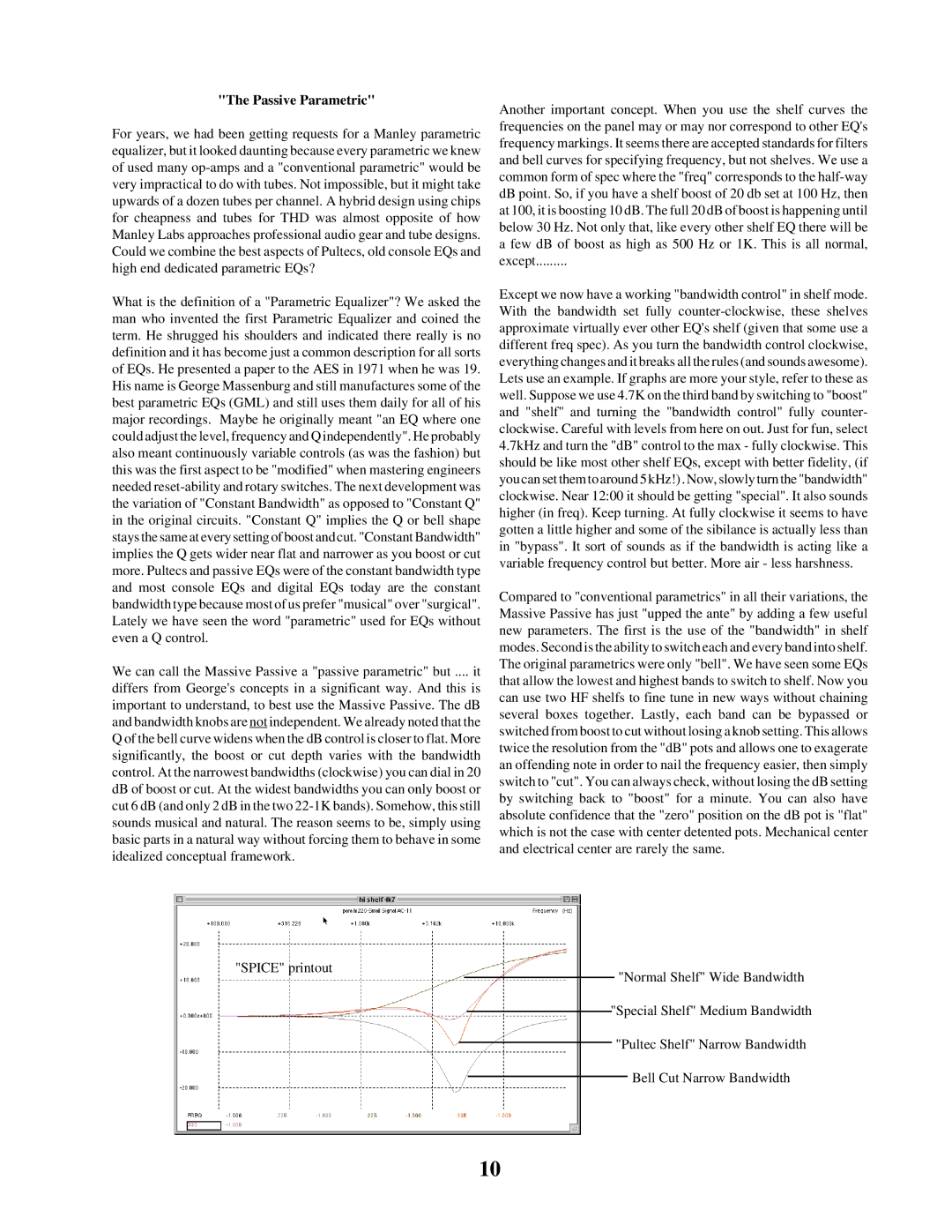

Except we now have a working "bandwidth control" in shelf mode. With the bandwidth set fully counter-clockwise, these shelves approximate virtually ever other EQ's shelf (given that some use a different freq spec). As you turn the bandwidth control clockwise, everything changes and it breaks all the rules (and sounds awesome). Lets use an example. If graphs are more your style, refer to these as well. Suppose we use 4.7K on the third band by switching to "boost" and "shelf" and turning the "bandwidth control" fully counter- clockwise. Careful with levels from here on out. Just for fun, select 4.7kHz and turn the "dB" control to the max - fully clockwise. This should be like most other shelf EQs, except with better fidelity, (if you can set them to around 5 kHz!) . Now, slowly turn the "bandwidth" clockwise. Near 12:00 it should be getting "special". It also sounds higher (in freq). Keep turning. At fully clockwise it seems to have gotten a little higher and some of the sibilance is actually less than in "bypass". It sort of sounds as if the bandwidth is acting like a variable frequency control but better. More air - less harshness.

Compared to "conventional parametrics" in all their variations, the Massive Passive has just "upped the ante" by adding a few useful new parameters. The first is the use of the "bandwidth" in shelf modes. Second is the ability to switch each and every band into shelf. The original parametrics were only "bell". We have seen some EQs that allow the lowest and highest bands to switch to shelf. Now you can use two HF shelfs to fine tune in new ways without chaining several boxes together. Lastly, each band can be bypassed or switched from boost to cut without losing a knob setting. This allows twice the resolution from the "dB" pots and allows one to exagerate an offending note in order to nail the frequency easier, then simply switch to "cut". You can always check, without losing the dB setting by switching back to "boost" for a minute. You can also have absolute confidence that the "zero" position on the dB pot is "flat" which is not the case with center detented pots. Mechanical center and electrical center are rarely the same.