ROUTING

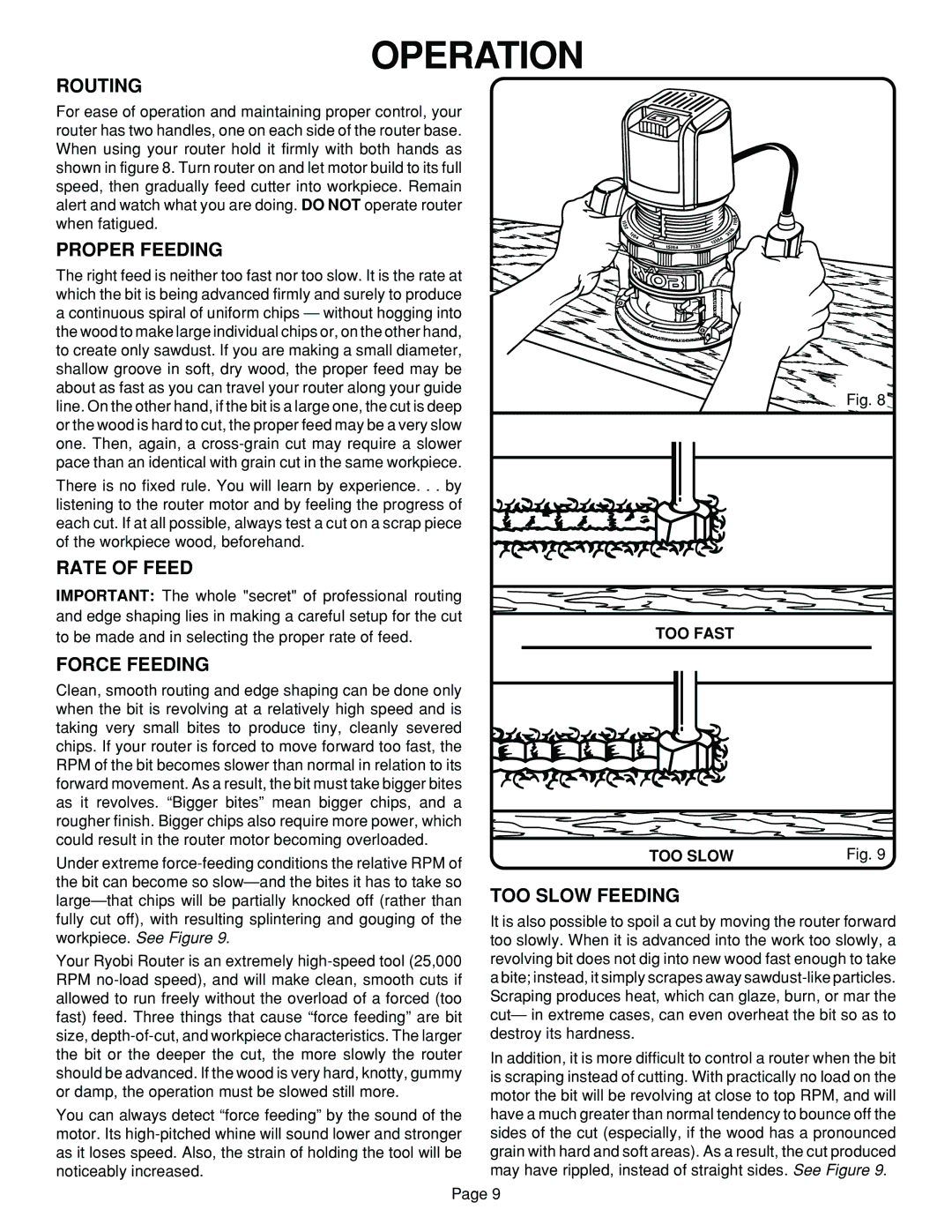

For ease of operation and maintaining proper control, your router has two handles, one on each side of the router base. When using your router hold it firmly with both hands as shown in figure 8. Turn router on and let motor build to its full speed, then gradually feed cutter into workpiece. Remain alert and watch what you are doing. DO NOT operate router when fatigued.

PROPER FEEDING

The right feed is neither too fast nor too slow. It is the rate at which the bit is being advanced firmly and surely to produce a continuous spiral of uniform chips — without hogging into the wood to make large individual chips or, on the other hand, to create only sawdust. If you are making a small diameter, shallow groove in soft, dry wood, the proper feed may be about as fast as you can travel your router along your guide line. On the other hand, if the bit is a large one, the cut is deep or the wood is hard to cut, the proper feed may be a very slow one. Then, again, a cross-grain cut may require a slower pace than an identical with grain cut in the same workpiece.

There is no fixed rule. You will learn by experience. . . by listening to the router motor and by feeling the progress of each cut. If at all possible, always test a cut on a scrap piece of the workpiece wood, beforehand.

RATE OF FEED

IMPORTANT: The whole "secret" of professional routing and edge shaping lies in making a careful setup for the cut to be made and in selecting the proper rate of feed.

FORCE FEEDING

Clean, smooth routing and edge shaping can be done only when the bit is revolving at a relatively high speed and is taking very small bites to produce tiny, cleanly severed chips. If your router is forced to move forward too fast, the RPM of the bit becomes slower than normal in relation to its forward movement. As a result, the bit must take bigger bites as it revolves. “Bigger bites” mean bigger chips, and a rougher finish. Bigger chips also require more power, which could result in the router motor becoming overloaded.

Under extreme force-feeding conditions the relative RPM of the bit can become so slow—and the bites it has to take so large—that chips will be partially knocked off (rather than fully cut off), with resulting splintering and gouging of the workpiece. See Figure 9.

Your Ryobi Router is an extremely high-speed tool (25,000 RPM no-load speed), and will make clean, smooth cuts if allowed to run freely without the overload of a forced (too fast) feed. Three things that cause “force feeding” are bit size, depth-of-cut, and workpiece characteristics. The larger the bit or the deeper the cut, the more slowly the router should be advanced. If the wood is very hard, knotty, gummy or damp, the operation must be slowed still more.

You can always detect “force feeding” by the sound of the motor. Its high-pitched whine will sound lower and stronger as it loses speed. Also, the strain of holding the tool will be noticeably increased.

OPERATION

TOO FAST

TOO SLOW FEEDING

It is also possible to spoil a cut by moving the router forward too slowly. When it is advanced into the work too slowly, a revolving bit does not dig into new wood fast enough to take

abite; instead, it simply scrapes away sawdust-like particles. Scraping produces heat, which can glaze, burn, or mar the cut— in extreme cases, can even overheat the bit so as to destroy its hardness.

In addition, it is more difficult to control a router when the bit is scraping instead of cutting. With practically no load on the motor the bit will be revolving at close to top RPM, and will have a much greater than normal tendency to bounce off the sides of the cut (especially, if the wood has a pronounced grain with hard and soft areas). As a result, the cut produced may have rippled, instead of straight sides. See Figure 9.

Page 9