During compressor shutdown, gravity, thermal action and refrigerant absorption can result in a refrigerant and oil mixture in compressor crankcase. Gravity flow can be prevented by the use of recommended loops, but thermal action and the absorp- tion of refrigerant by lubricating oil cannot be prevented by piping design.

For the above reasons, the compressor must be controlled during idle times by one of the following methods.

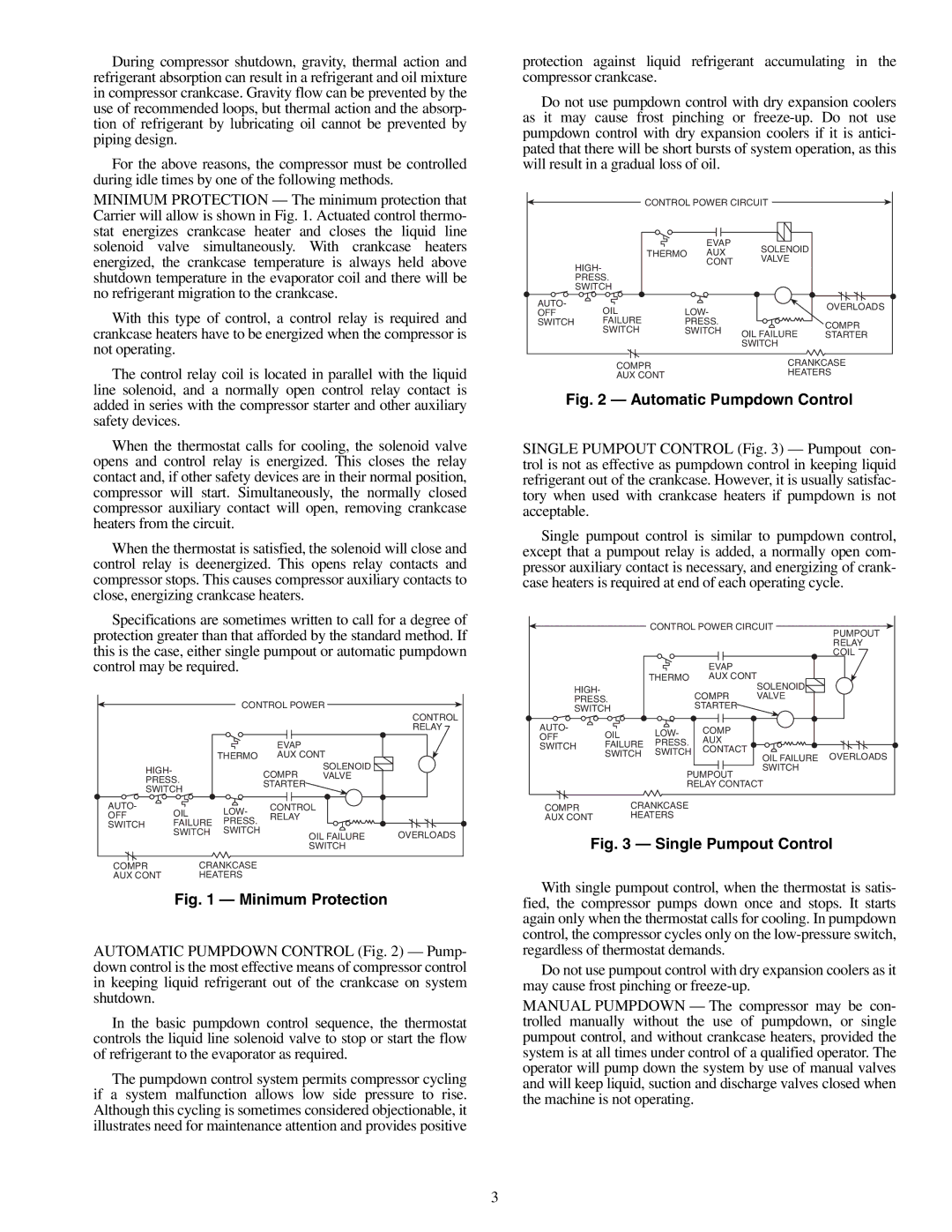

MINIMUM PROTECTION — The minimum protection that Carrier will allow is shown in Fig. 1. Actuated control thermo- stat energizes crankcase heater and closes the liquid line solenoid valve simultaneously. With crankcase heaters

protection against liquid refrigerant accumulating in the compressor crankcase.

Do not use pumpdown control with dry expansion coolers as it may cause frost pinching or

CONTROL POWER CIRCUIT

EVAP

THERMO AUX SOLENOID

energized, the crankcase temperature is always held above

HIGH-

CONT VALVE

shutdown temperature in the evaporator coil and there will be no refrigerant migration to the crankcase.

With this type of control, a control relay is required and crankcase heaters have to be energized when the compressor is not operating.

The control relay coil is located in parallel with the liquid line solenoid, and a normally open control relay contact is added in series with the compressor starter and other auxiliary safety devices.

When the thermostat calls for cooling, the solenoid valve opens and control relay is energized. This closes the relay contact and, if other safety devices are in their normal position, compressor will start. Simultaneously, the normally closed compressor auxiliary contact will open, removing crankcase heaters from the circuit.

When the thermostat is satisfied, the solenoid will close and control relay is deenergized. This opens relay contacts and compressor stops. This causes compressor auxiliary contacts to close, energizing crankcase heaters.

Specifications are sometimes written to call for a degree of protection greater than that afforded by the standard method. If this is the case, either single pumpout or automatic pumpdown control may be required.

CONTROL POWER

|

|

|

|

| CONTROL |

|

|

|

|

| RELAY |

|

|

| EVAP |

|

|

|

| THERMO | AUX CONT |

| |

HIGH- |

|

| COMPR | SOLENOID |

|

|

| VALVE |

| ||

PRESS. |

|

| |||

| STARTER |

|

| ||

SWITCH |

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

| ||

AUTO- | OIL | LOW- | CONTROL |

| |

OFF | RELAY |

|

| ||

SWITCH | FAILURE | PRESS. |

|

|

|

| SWITCH | SWITCH |

| OIL FAILURE | OVERLOADS |

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

| SWITCH |

|

COMPR | CRANKCASE |

|

|

| |

AUX CONT | HEATERS |

|

|

| |

Fig. 1 — Minimum Protection

AUTOMATIC PUMPDOWN CONTROL (Fig. 2) — Pump- down control is the most effective means of compressor control in keeping liquid refrigerant out of the crankcase on system shutdown.

In the basic pumpdown control sequence, the thermostat controls the liquid line solenoid valve to stop or start the flow of refrigerant to the evaporator as required.

The pumpdown control system permits compressor cycling if a system malfunction allows low side pressure to rise. Although this cycling is sometimes considered objectionable, it illustrates need for maintenance attention and provides positive

PRESS.

SWITCH

AUTO- | OIL | LOW- |

| OVERLOADS |

OFF |

| |||

|

| |||

SWITCH | FAILURE | PRESS. |

| COMPR |

| SWITCH | SWITCH | OIL FAILURE | |

| STARTER | |||

|

|

|

| SWITCH | |

COMPR | CRANKCASE | |

HEATERS | ||

AUX CONT | ||

|

Fig. 2 — Automatic Pumpdown Control

SINGLE PUMPOUT CONTROL (Fig. 3) — Pumpout con- trol is not as effective as pumpdown control in keeping liquid refrigerant out of the crankcase. However, it is usually satisfac- tory when used with crankcase heaters if pumpdown is not acceptable.

Single pumpout control is similar to pumpdown control, except that a pumpout relay is added, a normally open com- pressor auxiliary contact is necessary, and energizing of crank- case heaters is required at end of each operating cycle.

CONTROL POWER CIRCUIT

PUMPOUT

RELAY

COIL

|

|

| EVAP |

|

|

|

| THERMO AUX CONT |

| ||

HIGH- |

|

|

| SOLENOID |

|

|

| COMPR | VALVE |

| |

PRESS. |

|

| |||

| STARTER |

|

| ||

SWITCH |

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

| ||

AUTO- | OIL | LOW- | COMP |

|

|

OFF |

|

| |||

AUX |

|

| |||

SWITCH | FAILURE | PRESS. |

|

| |

CONTACT |

|

| |||

| SWITCH | SWITCH | OIL FAILURE | OVERLOADS | |

|

| ||||

|

|

|

| ||

|

| PUMPOUT | SWITCH |

| |

|

|

|

| ||

|

| RELAY CONTACT |

| ||

COMPR | CRANKCASE |

|

|

| |

AUX CONT | HEATERS |

|

|

| |

Fig. 3 — Single Pumpout Control

With single pumpout control, when the thermostat is satis- fied, the compressor pumps down once and stops. It starts again only when the thermostat calls for cooling. In pumpdown control, the compressor cycles only on the

Do not use pumpout control with dry expansion coolers as it may cause frost pinching or

MANUAL PUMPDOWN — The compressor may be con- trolled manually without the use of pumpdown, or single pumpout control, and without crankcase heaters, provided the system is at all times under control of a qualified operator. The operator will pump down the system by use of manual valves and will keep liquid, suction and discharge valves closed when the machine is not operating.

3