dramatic confrontation, in the second scene of Act Two.

Princess Turandot of China suffers from an icy heart, and a

jones toward men. Any male of royal blood may woo her, but

must answer three riddles. If his answers are correct, she

marries him; if they’re wrong, you guessed it: He dies. Every

prince who’s tried up to now has contributed his severed head

to Turandot’s collection; the Chinese nation, ruled by an

ancient, weary emperor, is caught up in the drama, with peo-

ple either turning cynical, or lusting for more blood.

Calaf, it won’t surprise any reader to learn, is the prince

who answers the riddles and melts Turandot’s heart. But first

she must defy him, explaining with frigid passion that the

whole scheme is designed to avenge a female ancestor who’d

been horribly violated, and then flinging a threat at the prince,

the kind of utterance that only makes sense in the unreal world

of fantasy (or opera): “The riddles are three, but death is one!”

She sings this, of course, in a phrase that rises to a high

note. “The riddles are three,” replies our game hero, taking the

musical arc even higher, “but life is one!” And then both of

them hurl their lines at each other, both singing at once, tak-

ing the music to the highest note yet. I would have thought

nobody, not even Richard Nixon, could have sung that music

without shameless excitement, if only because the high notes

won’t come out without some physical oomph behind them,

and because exuberance would be anyone’s natural reaction

after surging through them successfully. Like many other

great operatic moments, this one isn’t just music and drama,

but also an athletic feat.

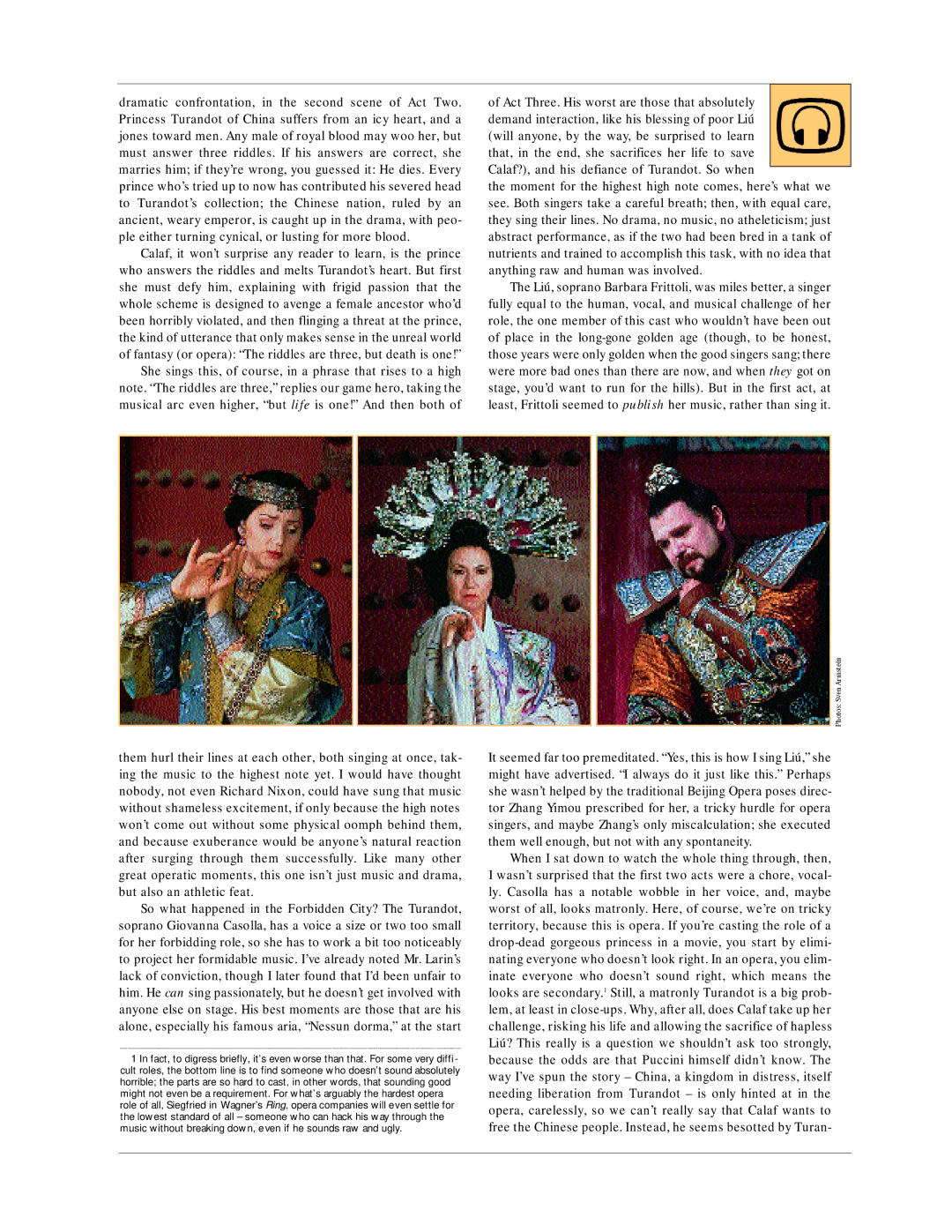

So what happened in the Forbidden City? The Turandot,

soprano Giovanna Casolla, has a voice a size or two too small

for her forbidding role, so she has to work a bit too noticeably

to project her formidable music. I’ve already noted Mr. Larin’s

lack of conviction, though I later found that I’d been unfair to

him. He can sing passionately, but he doesn’t get involved with

anyone else on stage. His best moments are those that are his

alone, especially his famous aria, “Nessun dorma,” at the start

1 In fact, to digress briefly, it’s even worse than that. For some very diffi - cult roles, the bottom line is to find someone who doesn’t sound absolutely horrible; the parts are so hard to cast, in other words, that sounding good might not even be a requirement. For what’s arguably the hardest opera role of all, Siegfried in Wagner’s Ring, opera companies will even settle for the lowest standard of all – someone who can hack his way through the music without breaking down, even if he sounds raw and ugly.

of Act Three. His worst are those that absolutely

demand interaction, like his blessing of poor Liú

(will anyone, by the way, be surprised to learn

that, in the end, she sacrifices her life to save

Calaf?), and his defiance of Turandot. So when

the moment for the highest high note comes, here’s what we

see. Both singers take a careful breath; then, with equal care,

they sing their lines. No drama, no music, no atheleticism; just

abstract performance, as if the two had been bred in a tank of

nutrients and trained to accomplish this task, with no idea that

anything raw and human was involved.

The Liú, soprano Barbara Frittoli, was miles better, a singer

fully equal to the human, vocal, and musical challenge of her

role, the one member of this cast who wouldn’t have been out

of place in the

those years were only golden when the good singers sang; there

were more bad ones than there are now, and when they got on

stage, you’d want to run for the hills). But in the first act, at

least, Frittoli seemed to publish her music, rather than sing it.

It seemed far too premeditated. “Yes, this is how I sing Liú,” she

might have advertised. “I always do it just like this.” Perhaps

she wasn’t helped by the traditional Beijing Opera poses direc-

tor Zhang Yimou prescribed for her, a tricky hurdle for opera

singers, and maybe Zhang’s only miscalculation; she executed

them well enough, but not with any spontaneity.

When I sat down to watch the whole thing through, then,

I wasn’t surprised that the first two acts were a chore, vocal-

ly. Casolla has a notable wobble in her voice, and, maybe

worst of all, looks matronly. Here, of course, we’re on tricky

territory, because this is opera. If you’re casting the role of a

nating everyone who doesn’t look right. In an opera, you elim-

inate everyone who doesn’t sound right, which means the

looks are secondary.1 Still, a matronly Turandot is a big prob-

lem, at least in

challenge, risking his life and allowing the sacrifice of hapless

Liú? This really is a question we shouldn’t ask too strongly,

because the odds are that Puccini himself didn’t know. The

way I’ve spun the story – China, a kingdom in distress, itself

needing liberation from Turandot – is only hinted at in the

opera, carelessly, so we can’t really say that Calaf wants to

free the Chinese people. Instead, he seems besotted by Turan-