signal (to spot them visually you’d need to perform a FOURIER TRANSFORM). AC mains frequency and its overtones are picked up by any wire, and some will always leak through a cable screen. The question is, when does it become audible?

Well, all other things being equal, the amount of mains hum picked up by a cable is independent of the signal level. Speaker lines run 50 or more volts, enough to diminish the effect of mains radiation to vanishingly small even with no screen. (In fact, at these voltages another effect comes into play: capacitive resistance. It is positively undesirable to use screened cable to wire an amp to a speaker. Speaker leads should be as thick and short as possible, with XLR or wound post terminals.)

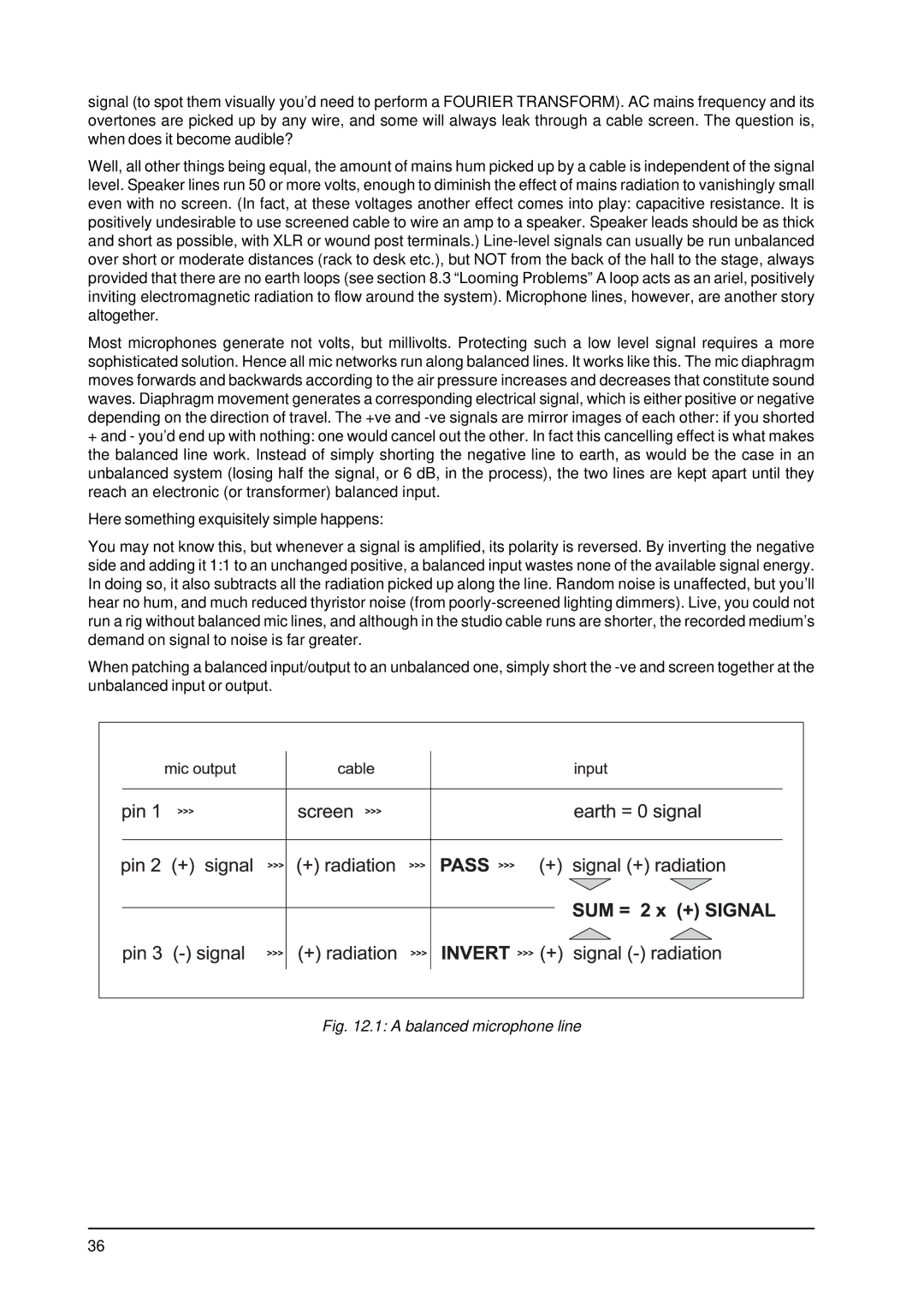

Most microphones generate not volts, but millivolts. Protecting such a low level signal requires a more sophisticated solution. Hence all mic networks run along balanced lines. It works like this. The mic diaphragm moves forwards and backwards according to the air pressure increases and decreases that constitute sound waves. Diaphragm movement generates a corresponding electrical signal, which is either positive or negative depending on the direction of travel. The +ve and

+and - you’d end up with nothing: one would cancel out the other. In fact this cancelling effect is what makes the balanced line work. Instead of simply shorting the negative line to earth, as would be the case in an unbalanced system (losing half the signal, or 6 dB, in the process), the two lines are kept apart until they reach an electronic (or transformer) balanced input.

Here something exquisitely simple happens:

You may not know this, but whenever a signal is amplified, its polarity is reversed. By inverting the negative side and adding it 1:1 to an unchanged positive, a balanced input wastes none of the available signal energy. In doing so, it also subtracts all the radiation picked up along the line. Random noise is unaffected, but you’ll hear no hum, and much reduced thyristor noise (from

When patching a balanced input/output to an unbalanced one, simply short the

Fig. 12.1: A balanced microphone line

36