IBM eServer zSeries 990 Technical Guide

Page

IBM eServer zSeries 990 Technical Guide

Second Edition April

This document created or updated on April 7

Iii

Iv IBM eServer zSeries 990 Technical Guide

Contents

6947TOC.fm

6947TOC.fm

Appendix B. Fiber optic cabling services

6947spec.fm

Eckd

Trademarks

First Edition authors

Team that wrote this redbook

Comments welcome

Become a published author

IBM zSeries 990 overview

Balanced system design

Escon

Introduction

Z990 models

Model upgrade paths

General rules

Concurrent Processor Unit PU conversions

System functions and features

Processor

Model downgrades

Self-Timed Interconnect STI

Memory

Channel Subsystem CSS

Spanned channels

Physical Channel IDs PCHIDs and Chpid Mapping Tool

Cage

7 I/O connectivity

Up to 120 Ficon Express channels

Up to 1024 Escon channels

Ficon Cascaded Directors

Ficon CTC function

1000BASE-T Ethernet

Checksum Offload for Linux and z/OS when Qdio mode

OSA-Express

Gigabit Ethernet

OSA-Express ATM

Cryptographic CP Assist for cryptographic function

Parallel channels and converters

Token Ring

PCI X-Cryptographic Coprocessor Pcixcc feature

PCI Cryptographic Accelerator feature Pcica

Parallel Sysplex support

Internal Coupling IC

ICB-2 Integrated Cluster Bus

ICB-3 Integrated Cluster Bus

ICB-4 Integrated Cluster Bus

Hardware consoles

Intelligent Resource Director IRD

On/Off Capacity Upgrade on Demand On/Off CoD

Concurrent upgrades

Capacity Upgrade on Demand CUoD

Customer Initiated Upgrade CIU

32 CPS

Performance

Software

Reliability, Availability, Serviceability RAS

Traditional database/transaction workloads

Unix System Services

ZSeries File System zFS

OS/390 & z/OS

Software support

Compatibility and exploitation

Linux on zSeries and Linux for S/390

Linux

Software pricing

VSE

Summary

System structure and design

Book concept

System structure

Cooling

Power

Hybrid cooling system

Models

Memory Sizes

New build 2084 physical memory card distribution

Memory sparing

Memory upgrades

Book replacement and memory

Ring Topology

MCM

MCM

Connectivity

STI connectors Book front view

Book upgrade

Frames and cages

Book replacement and connectivity

Frame

Cages

Capacitors

MCM

SC chip

PU, SC, and SD chips

SD chip

IBM 2084-A08 IBM 2084-B16 IBM 2084-C24 IBM 2084-D32

System design

Design highlights

Book design

12 Logical book structure

Dual External Time Reference

Processor Unit design

Superscalar processor

Asymmetric mirroring for error detection

CP Assist for Cryptographic Function

Compression Unit on a chip

Without BHT With BHT

Processor Branch History Table BHT

Instruction grouping

Ieee Floating Point

Translation Lookaside Buffer

Instruction fetching and instruction decode

Processor unit functions

Integrated Facilities for Linux

Central Processors

Dynamic ICF Expansion

Internal Coupling Facilities

Dynamic Coupling Facility Dispatching

ZAAPs and Lpar definitions

ZSeries Application Assist Processors

Purpose of a zAAP

Software support

System Assist Processors

Optional additional orderable SAPs

Processor unit characterization

Reserved processors

Optionally assignable SAPs

Sparing rules

Transparent CP, IFL, ICF, zAAP, and SAP sparing

Application preservation

Dynamic SAP sparing and reassignment

Dynamic Memory sparing

Memory design

Partial Memory Restart

Memory allocation

Expanded storage ES

Central storage CS

Lpar single storage pool

Hardware System Area HSA

Modes of operation

VSE/ESA

Logical Partitioning overview

Processors

Channels

Memory

Logically Partitioned Mode

Dynamic Add/Delete of a logical partition name

Model configurations

ZAAP

Upgrades

Unassigned CP

Unassigned IFL

Z990 Models 2084-A08 2084-B16 2084-C24 2084-D32

Software models

Z990 Models Software

PU conversions

From

Software model MSU values

Software MSU/ Pricing Model

Hardware Management Console and Support Elements

Storage operations

Operating

ESA/390 mode

Definition Definable

Architecture mode

ESA/390 TPF mode

Coupling Facility mode

Linux Only mode

Lpar storage granularity

Reserved storage

12 I/O subsystem

Lpar Dynamic Storage Reconfiguration DSR

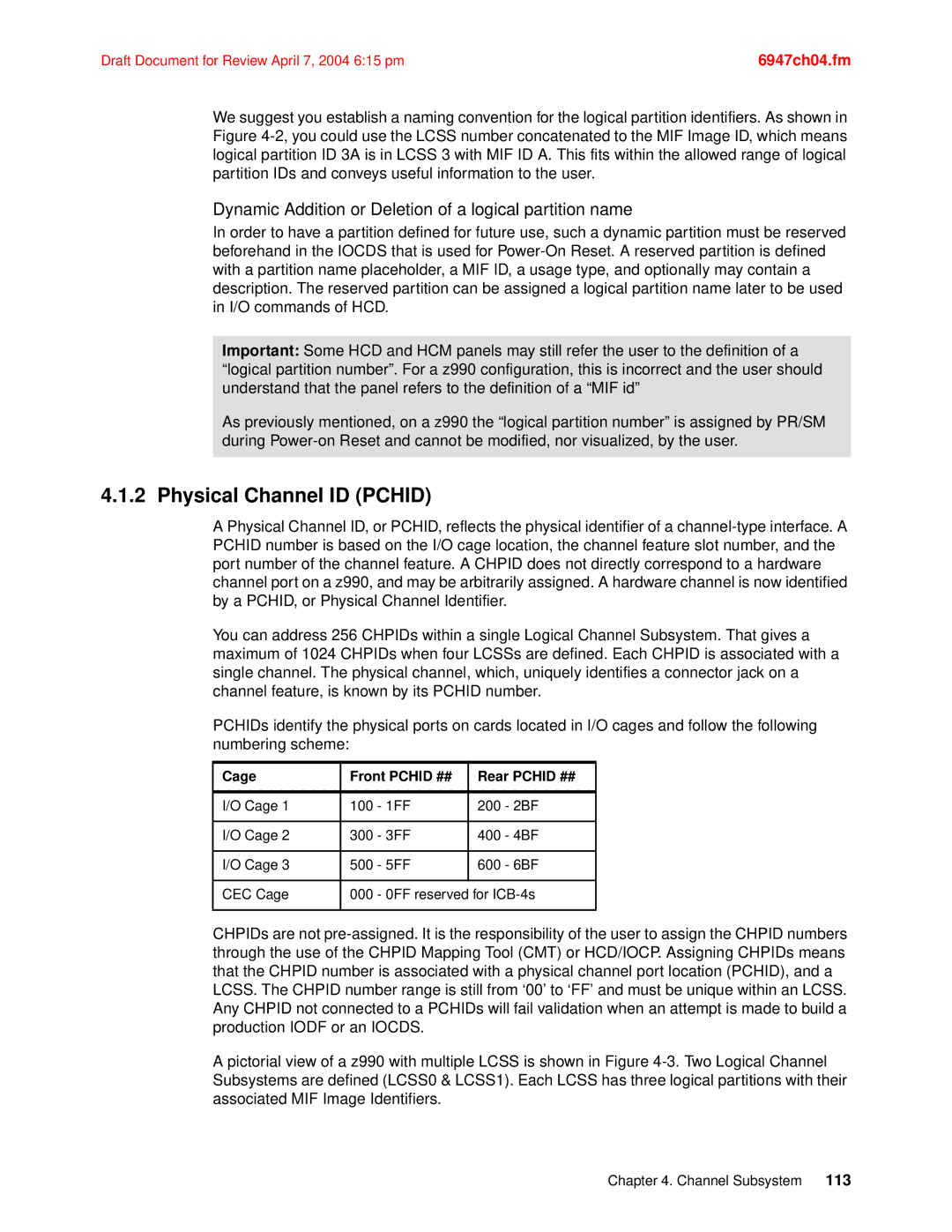

Cage Front Pchid ## Rear Pchid ##

Channel Subsystem

Logical Channel Subsystem Lcss

Physical Channel ID Pchid

O system structure

Overview

CEC Cage 1st I/O Cage standard

I/O cages

Domain Slots in domain

Board

Z990 Model Number of books Number of MBAs Number of STIs

STIs and I/O cage connections

Cage

ESTI-M card

STI-2 Extender card

Balancing I/O connections

STI-3 Extender card

STI Links Cards

STI links balancing across books and MBAs

2084-B16 CEC Cage

Book

2084-D32 CEC Cage

STI Rebalance feature Feature Code

Cage

Upgrade example with the STI Rebalance feature FC

STIs

Port balancing across MBAs and books

Card types Feature Codes FC

I/O and cryptographic feature cards

1 I/O feature cards

Feature cards no longer supported

Cryptographic feature card no longer supported

Cryptographic feature cards

Cryptographic card types Feature Codes FC

PCHIDs 121 131 Slots

Physical Channel IDs PCHIDs

Pchid Report example

CEC cage book Pchid numbers

Z990 Chipd Mapping Tool CMT

Connectivity

6947ch03.fm

Spanned and Shared channels

Feature code Feature name Connector type Cable type

Features cables and connectors

Escon channel

Z990 16-port Escon feature

Escon channel port enablement feature

Port Escon channel sparing

Fiber Quick Connect FQC for Escon Quick Connect

Ficon Express LX feature

Ficon Express features

Ficon channel

Ficon Express SX feature

Ficon channel in Fibre Channel Protocol FCP mode

Z990 adapter interruptions enhancement for FCP

OSA-Express adapter

Z990 FCP Scsi IPL feature enabler FC

Z990 FCP concurrent patch

OSA-Express GbE SX feature code

OSA-Express GbE LX feature code

OSA-Express GbE LX feature code 2364, upgrade only

OSA-Express 1000BASE-T Ethernet feature code

OSA-Express GbE SX feature code 2365, upgrade only

OSA-Express Integrated Console Controller OSA-ICC

OSA-Express Fast Ethernet feature code 2366, upgrade only

OSA-Express Token Ring feature code

Checksum offload for IPv4 packets when in Qdio mode

HiperSockets function

Z990 coupling link features

Coupling Facility links

Z990 adapter interruptions enhancement for Qdio

RPQ 8P2197 Extended distance option

ISC-3 link

Mode

ICB-4 link

ICB-3 link

ICB-2 link

IC links

External Time Reference ETR feature

Z990 ICB links summary

Pcix Cryptographic Coprocessor Pcixcc feature

Cryptographic features

PCI Cryptographic Accelerator Pcica feature

6947ch03.fm

109

Channel Subsystem

Logical Channel Subsystem structure

Multiple Logical Channel Subsystem Lcss

Logical partition number

Multiple Image Facility MIF

Logical Partition ID

Logical partition identifier

MIF Image ID Mifid

Logical partition name

Dynamic Addition or Deletion of a logical partition name

Physical Channel ID Pchid

Z990 Lcss connectivity

Channel spanning

IBM Configurator for e-business e-Config

Lcss configuration management

Hardware Configuration Dialog HCD

IBM z990 Chpid Mapping Tool CMT

1 z990 configuration management

Z990

LCSS-related numbers

6947ch04.fm

119

Cryptography

Cryptographic Synchronous functions

Cryptographic function support

Cryptographic Asynchronous functions

Cryptography

CP Assist for Cryptographic Function Cpacf

Z990 Cryptographic processors

Pcix Cryptographic Coprocessor Pcixcc

PCI Cryptographic Accelerator Pcica feature

Pcix Cryptographic Coprocessor feature

Cryptographic hardware features

Crypto

Configuration rules

Pcica feature

4 z990 cryptographic feature codes

TKE workstation feature

Cryptographic features comparison

Functions or Attributes

Private keys Public Key Encrypt PKE support for MRP function

Software requirements

6947ch05.fm

Operating system

6947ch05.fm

133

Software support

Z/OS software support

Operating system support

Compatibility support for z/OS

Compatibility support requirements

Z990 Compatibility for selected OS/390, and z/OS releases

Z990

Compatibility support restrictions

OS V1.5 Support

OS V1.4 z990 Compatibility Support feature

OS V1.4 z990 Exploitation Support feature

Exploitation support for z/OS

Processors within a single logical partition

Dynamic addition and deletion of a logical partition name

ZSeries Application Assist Processor zAAP

JVM

Automation changes

HCD support

SMF support

Ickdsf requirements

RMF support

Automation

Icsf support

Additional exploitation support considerations

Standalone dump

D M=CPU command output

Extended Channel Measurement Block

Switch ID =

Greater than 15 logical partitions

Z/VM software support

Dynamic activates for hardware changes

Dynamic Chpid management

TPF software support

Z/VSE and VSE/ESA software support

Linux software support

V1.4

Summary of software requirements

Summary of z/OS and OS/390 software requirements

Software Requirements OS/390 V1.6 a

V4.1

Software Requirements

Linuxon

V5.1 V4.4 V3.1

OSA-ICC

Workload License Charges

Processor Identification

Concurrent upgrades considerations

Version CPU identification number Machine Code Type number

Channel to Channel links

153

Sysplex functions

Sysplex LPARs

Parallel Sysplex

Parallel Sysplex described

Sysplex LPARs CF02

Systems management

Continuous application availability

High capacity

Dynamic workload balancing

Single system image

Resource sharing

Message Time Ordering

Sysplex configurations and Sysplex Timer considerations

Sysplex and Coupling Facility considerations

Parallel Sysplex summary

6947ch07.fm

Example 7-1 Display ETR

Cfcc enhanced patch apply

Coupling Facility and Cfcc considerations

Minimum software levels a

Cflevel

Link Type Z990 Max

Coupling Facility link connectivity

Link Type Z990 Max Maximum number of links per z990

Peer mode links

Meaning of Partition

ICF processor assignments

Function Setup

Z990 Dynamic CF Dispatching shared CPs or shared ICF PUs

Dynamic CF dispatching and dynamic ICF expansion

Benefits

System-managed CF structure duplexing

CF Structure Duplexing

Configuration planning

Z800/z900/z990/z890/G5/G6z800/z900/z990/z890/G5/G6

GDPS/PPRC

Geographically Dispersed Parallel Sysplex

ZSeries

GDPS/PPRC HyperSwap

Unplanned HyperSwap

Planned HyperSwap

Business Continuity for Linux guests

GDPS/PPRC Management for Open Systems LUNs

GDPS/PPRC over Fiber Channel links

Gdps FlashCopy V2 support

GDPS/XRC

Application

Gdps and Capacity Backup CBU

Recovery

Site

IRD overview

Intelligent Resource Director

Lpar CPU management

Value of CPU management

Dynamic Channel Path Management

Value of Dynamic Channel Path Management

Channel Subsystem Priority Queueing

Value of Channel Subsystem Priority Queueing

WLM and Channel Subsystem priority

Workload type Priority

Disabling Dynamic Channel Path Management

Automatic I/O interface reset

Special considerations and restrictions

Unique Lpar cluster names

System automation I/O operations

References

6947ch07.fm

185

Capacity upgrades

Concurrent PU conversions

Concurrent upgrades

Licensed Internal Code LIC-based upgrades

Concurrent hardware installation upgrades

Planned upgrades

Model upgrades

Function Upgrades Via Type Process

Capacity Upgrade on Demand CUoD

Unplanned upgrades

Capacity upgrade functions

6947ch08.fm

CUoD + 1 CP + 2 IFLs

CUoD for processors

CUoD for memory

CUoD + 16 GB + Model upgrade

+ 8 Escon

CUoD for I/O

Plan Ahead concurrent conditioning

Customer Initiated Upgrade CIU

CIU Registration and Agreed Contract for CIU

Internet

Ordering

Order and fulfillment process

CIU order example

Z990 Model Conversion screen

Activation

On/Off Capacity on Demand On/Off CoD

CIU upgrade selection screen

6947ch08.fm

Initiation

Termination

Activation/Deactivation

Repair capability during On/Off CoD

Capacity BackUp CBU

Upgrade Capability during On/Off CoD

Software

6947ch08.fm

Activation/deactivation of CBU

Image upgrades

CBU activation

CBU deactivation

Capacity BackUp operation example

Automatic CBU enablement for Gdps

CBU testing

Processors

Nondisruptive upgrades

Memory

Upgrade scenarios

PCI Cryptographic coprocessors

LP1 LP2

Shared logical partitions upgrade

LP1 LP2 LP3

Dedicated and shared logical partitions upgrade

Shared partitions and zAAP upgrade

LP1 LP2

Dedicated, shared partitions and IFL upgrade

LP2

Dedicated, shared partitions and ICF upgrade

Reasons for disruptive upgrades

Planning for nondisruptive upgrades

Recommendations to avoid disruptive upgrades

Capacity planning considerations

Considerations when installing additional books

Additional performance improvements for e-business

Balanced system design

16 shows a two-book z990 server logical view

Multi-book structure

Superscalar processors

Book

Secure encrypted transactions with higher performance

Integrated hardware and system assists

ZSeries Application Assist Processors zAAPs

Cryptographic function on every Processor Unit PU

Performance assists for Linux and z/VM

Capacity measurements

Internal Throughput Rate ITR and ITR Ratio Itrr

Large Systems Performance Reference Lspr

Lspr workloads for z990

Lspr workloads prior to z990

Operating system Workload type Workload description

Lspr workloads for z990 Lpar Mode

6947ch08.fm

OLTP-T

New predefined z/OS workload mixes

Z990 Lspr tables

229

Environmentals

Power consumption

Power and cooling requirements

Internal Battery Feature

Cooling requirements

Weights

Emergency power-off

Configuration

Frames Width mm Depth mm Height mm

Dimensions

233

Appendix A. Hardware Management Console HMC

LAN

LAN

Z990 Hardware Management Console

Token-Ring LAN

Token ring only wiring scenario

Additional token ring only wiring scenario

Ethernet only one-path wiring scenario

Additional connections to the Ethernet LAN

Figure A-5 Ethernet only one path wiring scenario

Ethernet only two-path wiring scenario

Figure A-7 Ethernet only two-path wiring scenario

Token ring and Ethernet wiring scenario

Additional connections to the Token Ring LAN

Remote operations

Z990 HMC enhancements

Support Element

Z990 HMC Integrated 3270 Console

Increased Console tasks performed log

Optional strict password rules supported

Z990 HMC Integrated Ascii Console support

Enhanced logging facilities

SNA Operations Management for Operations Automation

6947axA.fm

247

Appendix B. Fiber optic cabling services

Fiber optic cabling services from IBM

249

Summary

6947axB.fm

Other publications

IBM Redbooks

251

Online resources

How to get IBM Redbooks

253

Glossary

EMIF. See Escon Multiple Image Facility

Fiber optic cable. See optical cable

ESA/390. See Enterprise Systems Architecture/390

IPL. See initial program load

Fiber

PTF. See program temporary fix

6947glos.fm

6947glos.fm

IBM eServer zSeries 990 Technical Guide

IBM eServer zSeries Technical Guide

263

Index

GDPS/PPRC

Pcicc

SAP

Page

IBM eServer zSeries 990 Technical Guide