This document supports firmware version 2.2 and above

Page

Warranty

TEK-WIDE

How to Reach Customer Service

Table of Contents

Tutorial

Table of Contents

Menus

Theory of Operation Glossary Glossary-1 Index Index-1

Gpib

List of Figures

List of Tables

Safety

Behavior of Outputs Turning Power On or Off

SMA Connectors

Do Not Remove Instrument Covers

Static Sensitive Device Notice

Conventions

How This Manual is Organized

Related Manuals

Xvi

Getting Started

Features

GB1400 Pattern Generator and Error Detector

Applications

Symmetrical, Low-Jitter Output Waveforms

Prbs Or User-Defined Test Patterns

Sample Applications

Auto Search For Easy Setup

Adjustable Inputs For Maximum Flexibility

Powerful Analysis And Reporting Functions

Burst Mode

GigaBERT GB1400

Ordering Information

GB1400T

GB1400R

GB Comparison GB660/CSA907A GB700 GB1400 Feature Tx and Rx

GB1400 with Burst Option

GB1400 Instrument Configurations Standard and Burst Option

Procedure

Initial Self-Check Procedure

Page

Operating Basics

Functional Overview

Example, Bert Application

Bert Basics GB1400

Clock Data

Front Panel, GB1400 Generator Tx

Controls, Indicators and Connectors

Front Panel, GB1400 Analyzer RX

1405000 PN23

Display Formats

Generator Tx Display

Frequency kHz Pattern Output

Delay/ Memory

Frequency kHz Error Rate Totalize

1405000 0E-06 2410538 PN23

Analyzer RX Display

Page

Generator Output Connectors Section

Outputs and Inputs

= clock bar = not clock

Generator Clock Section

Generator Output Section

Changing the Line Fuse

Generator Rear Panel

Analyzer Input Section

Analyzer Monitor Section

Analyzer Rear Panel

Connectors, Terminations, and Levels

DATA/DATA BAR

Power Switches

Controls and Indicators

Reset to Factory Default

View Angle and Panel Lock Keys

Gpib Section Controls

Pattern Controls and Function Keys

Analyzer Inputs

Function Soft Keys F1, F2, F3, and F4

Generator Error Inject Section

Affected Input Allowable Control

Sync Loss

Analyzer Error History Section

Analyzer Sync Controls

Analyzer Error Detection Section

Burst Mode Option

Specifications for Burst Mode

Burst Mode Usage

Data Value

Transmitter Burst Mode Option

Display Setting

Pecl Option for GB1400 Tx

ECL Levels Pecl Levels

Key Feature of Tutorial

Basic Bert testing with the GB1400

Objective of Tutorial

Equipment Required

Instrument Connections and Controls

Setup units with default settings

Connect the Generator to the Analyzer

Setup Generator for PRBS-23 Mode

Setup Analyzer for AUTO-SEARCH Operation

Turn off Auto Search and change Generator Outputs

Change the Prbs pattern type

Key several times to setup the analyzer for totalize

Your data signal

Data signal not detected. Selected

Error Rate display shows no Data or a 50% Error Rate

You are starting to detect the data signal

This Concludes the Tutorial

Two Auto Search Synchronization Methods

Applications

Phase

Application Note Auto Search Synchronization

Auto Search will find the Data Delay

Auto Search Algorithm Fast Method

Auto Search will find the Data V-THRESHOLD voltage

II. Auto Search Algorithm BER Method

Auto Search will find the Data Pattern and Polarity

Auto Search will then attempt to find the Data Pattern

Auto Search will determine the Data Delay

Page

Delay Specifications

Consideration In Determining The Eye Data Width

Consideration In Determining The Data Eye Center

Fiber Optic Link Test Example

GB700/ GB1400 Optical Component Test

Fibre Channel Link Testing Parallel and High-speed Serial

Qpsk

Testing Qpsk Modems, I & Q

Channel Bert

Qpsk BER Testing using Prbs Data for 2-Channel I & Q

Application Example

Reference

Menu Overview

Turning Instrument Power ON/OFF

Functions Common to Generator TX and Analyzer RX

Selecting 115 VAC or 230 VAC Operation

Selecting a Pattern

Recalling the Default Setup

Locking the Front Panel

Pattern Definitions

Selecting Prbs Patterns

Selecting the Active Pattern

Selecting the Current Word Pattern

Prbs 2n-1 Test Patterns

Word

Selecting RECALLing a Saved Word Pattern

Word Patterns

Creating Word Patterns Using Front Panel Controls

Basics

Standard Instruments

Instruments Equipped with 1-Mbit Option

Creating Word Patterns Using Menus

Length Fill

Order

Creating Word Patterns Under Remote Control

Recalling Word Patterns 1-Mbit Memory Option

Saving Word Patterns 1-Mbit Memory Option

Clock Source and Frequency

Generator TX Functions

External Clock Input

Clock Source

Recalling a Frequency

Saving a Frequency

Overview

Data and Clock Outputs

Generator Clock and Data Output Equivalent Circuits

Amplitude and Baseline Offset

Output Setup Rules vs. Termination Impedance

Logically Inverting Output Data D-INV

Procedure for Differential Operation TX only

Procedure for Single-ended Operation TX only

Single-ended or Differential Operation

Pattern Sync and CLOCK/4 Outputs

Selecting an Error Inject Mode

Error Injection

Error Inject Input

Procedure to Control Error Injection Mode

Data Inhibit Logic

Disable Key

Automatic Setup Functions Sync

Analyzer RX Functions

Auto Search Key

Auto Search With Prbs Patterns

Actions Taken by Analyzer when Synchronization is Lost

How to Disable Automatic Pattern Resynchronization

Relationship between Auto Search and Disable

Auto Search with Non-PRBS Patterns

Procedure to Set Sync Threshold

Synchronization Lock Threshold

Synchronization Threshold

Input Parameters

Clock, Data, and Reference Data Inputs

How F2 and F3 Determine Which Input Can be Set Up

Input Data Delay

Procedure to Add Delay

Controls

Procedure for Selecting Input Termination

Input Termination

Input Terminations for CLOCK, DATA, and REF Data

Input Decision Threshold

Logically Inverting Input Data

Input Threshold Range as a Function of Termination

Selecting the Reference Data Mode

Procedure for Selecting the Reference Data Mode

Singled-ended or Differential Operation

Monitor Outputs

Output Setup

BER

Error Detection Set Up

How Window Results Are Measured

How Totalize Results are Measured

Window Measurement Process

How Test Results Are Measured

Test Measurement Process

Totalize Process Set Up

Display Mode Totalize, Window, or Test

Procedure to Select a Results Display Mode

How to Tell Which Display Mode is Active

Procedure

Window Process Set Up

Test Process Set Up

Procedure to View Desired BER and Bit Error Results

BER and Bit Errors

Viewing Results

All Other Results Test Process only

Printing Results Reports

Basic Report Setup Procedure

Example Analyzer Setup Report

Analyzer Setup Report

Procedure to Enable or Disable End-of-Test Reports

End-of-Test Reports

Example End-of-Test Report

Procedure to Enable or Disable End-of-Window Reports

End-of-Window Reports

Example End-of-Window Report

Example On-Error Report

On-Error Reports

Procedure to Enable On-Error Reports

Procedure to Generate an On-Demand Test Summary Report

Result Definitions

BER = TE / TB

All Other Results Test Intervals Only

ES = TSE US

Analyzer performance history indicators are

Error History Indicators

Located in the Error History section of the front

Panel. These indicators will latch on when the indicated

Procedure To Set Up the Audio Alert Function

Analyzer Error Messages

Clear Control

Audio Beeper Function

Procedure for Starting the Test Measurement Process

Procedure for Stopping the Test Process

Starting and Stopping Measurements

Starting New Totalize and Window Measurement Intervals

Example Procedure Illustrating Menus and Functions

Functions Performed Using the Menu System

Menus

Menu and Function Pages

More Length Mode Report F1ESC F4SET Test Mode = Untimed

F1ESC F4SET Reports on = EOT/ERROR

General Rules for Using the Menu System

10. Menu Descriptions

Menu Summaries

11. Analyzer Menu System Overview

Word

12. Generator Menu System Overview

Menu Function Definitions

Word AT ddddd = bbbbbbbb

F1ESC F2- -F3 F4SET

Word Edit Edit

Format

F1ESC F2- -F3 F4SET LENmmmmm Bytes + n Bits

Word Length Length

Word Length

Word Fill Fill

Fill Word Memory WITHhh

F1ESC F4SET Word Order = ccc First

Word Order Order

Word Order

Word Sync Thres LEVEL= d

Word Synchronization Threshold Sync

Word Sync

Buffer

Buffer

Fast BER

Auto

F1ESC F2- -F3 F4SET Test Length = hhmmss

Test Length Length

Test Length

F1ESC F4SET Test Mode = ccccccc

Test Mode Mode

Test Mode

F1ESC F4SET Reports on = ccccccccc

Test Reports Report

Test Report

F1ESC F4SET Error Threshold = eeeee

Test Threshold Thres

Test Thres

On Error Squelch = ccc

Test Squelch Squel

Test Squel

Test Print

Test Print Print

F1ESC F4SET result namecount %

Test View Previous VIEW-PRE

Test VIEW-PRE

Test VIEW-CUR

Test View Current VIEW-CUR

F1ESC F4SET Window Mode = ccccccc

Window Mode Mode

Window Mode

F1ESC F4SET Window LEN = 1.0eEE Bits

Format

Window Interval in Bits Bits

Window Bits

F1ESC F2- -F3 F4SET Window LEN = hhmmss

Window Interval in HrsMinSec Second

Window Second

END of Window Print = ccc

Window Reports Report

Window Report

Baud = dddd

RS-232 Baud Rate Baud

Baud

F1ESC F4SET Parity = cccc

RS-232 Parity Parity

Parity

Size = d

RS-232 Data Bits Size

Size

F1ESC F4SET EOL = ccccc

RS-232 End-of-Line Char. EOL

EOL

F1ESC F4SET XON/XOFF Enable = ccc

RS-232 Xon/Xoff XON/XOFF

XON/XOFF

F1ESC F4SET RS232 Echo Enable = ccc

RS-232 Echo Echo

Echo

F1ESC F4SET Terminator = cccccc

Util Option

Utility Option Option

Util VER

Utility Version VER

F1ESC F2- -F3 F4SET Date = mmm dd yy

Time Option Date

Date

F1ESC F2- -F3 F4SET Time = hhmmss

Time Option Time

Time

Reference

Appendices

Internal Clock Source

GB1400 Generator TX

External Clock Source

SMA

Data Output True and Complement

Data Patterns

Error Injection

Rear Panel Auxiliary Outputs Phase A, Phase B, Clock/2

Clock Output True and Complement

NRZ-L

AC-Power Requirements

RS-232 and Gpib Interfaces

Mechanical

GB1400 Analyzer

Clock Input

Data Input

Reference Data Input

Synchronization

AUX

BER

Measurements

Printer Interface

Specifications

Bert Primer/ Technical Articles

Bert Definition

Bert used to test physical layer

Bert Building Blocks

Prbs Patterns

Bert Pattern Generation

Prbs

Doutput

Prbs Generation Circuits a few sample diagrams

Other Tx Patterns

Bert Clock

Bert Receiver or Error Analyzer Components

Output Amplifiers

Data Coding, NRZ

Received Data Pattern Reference

Error Comparator

Data Input Amplifiers

BER Computation

Stress Testing

Confidence Requires Collecting Many Errors

Confidence Level in BER Measurement

Additional Reading

Other Bert Features

Eye Width Measurement

Auto-Synch

Error Insertion

Pattern Lock

Pattern Loading Software

Jitter Generation

Bit error rate testing

How long is long enough?

BER

Ideal pulse

Stressing through pattern generation

Bert Technical Articles

Bert Technical Articles

Bert Technical Articles

Ensure Accuracy Of Bit-Error Rate Tests

Page

Bert

Supplying Data Patterns

Noise-Margin Stressing

Μ F Avergage = Average =

Page

Data Patterns Stored

Data patterns for clock recovery stressing

Examining Jitter

+ Peak

2f BΦ θif B

Jitter Tolerance

Amplitude UI peak-to-peak Frequency

Bert Affects Accuracy

Abstract

Example of Error Rate Measurement

= n / T

BER Measurement Inaccuracy versus Test Time

Inaccuracy 95% = 2 σ / n ≈ 2/ n

Reduced Test Time by Stressing

Testing for an Upper Limit on Error Rate

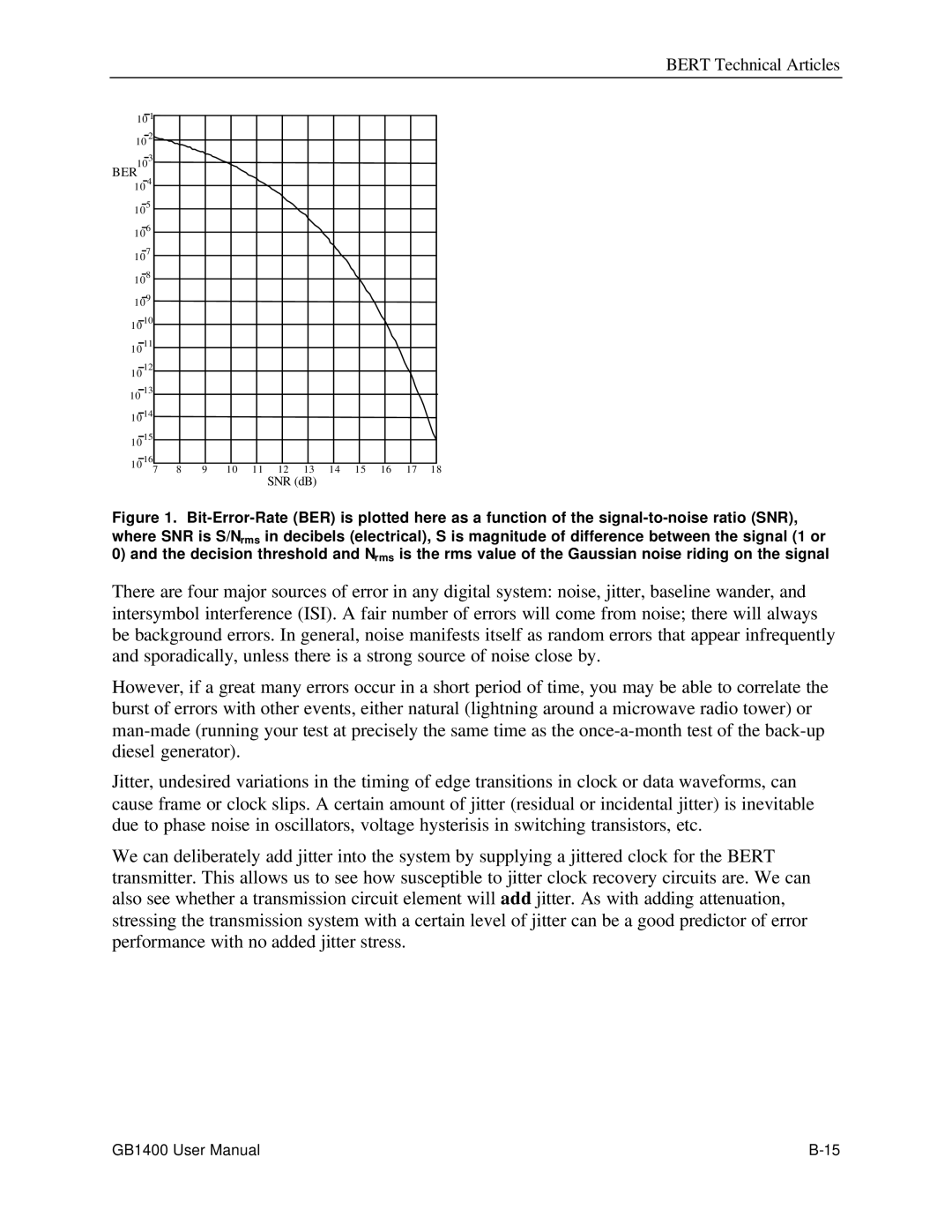

SNR = 20 log S / N rms

Attenuation dB

BER

Example

Example

BER

Summary

Pn = rT n e−rT . n

Poisson Error Process

BER

Biography

Type of Commands Starts on

Remote Commands

Overview

DATATHRES?

Datathres

Command Line Terminator

Command Line Rules

Setting Arguments Outside of Legal Ranges

Command Examples

Command Summary Alphabetical

Bytesync n Analyzer only Bytesync?

Remote Commands

Rescurrate?

Tse?

Ese n

Cls

Ese?

Esr?

Idn?

Lrn?

Opc

Opc?

Sre n

Rst

Stb?

Sre?

Wai

Tst?

Tse v Analyzer Only

Tse? Analyzer Only

Tsr? Analyzer Only

Datainvert onoff

Datainvert?

Datapattern prbs word rdata

Datapattern?

Prbslength

Prbslength?

Recallword m

Saveword m

Wordbits l, b1 b2

Wordbits?

Wordlength l

Wordmemlen m, l

Wordmemord m, msb lsb

Wordmemord?

Wordmemord? m

Wordmemory? m

Wordmemory m, l, b1, b2

Example Wordorder lsb

Wordorder msb lsb

Page

Memory allocation for Word Memory storage

Wordorder?

Wordmemory?

Gpibaddress

Gpibaddress?

Gpibbus offbus talklisten

Rsecho onoff

Gpibbus?

Rsecho?

Rspmtlf onoff

Rsprompt s

Rspmtlf?

Rsxonxoff onoff

Rspmtlf on

Rsxonxoff?

Wordmemory 0, 16, #HAA, #HBB Wordmemory 1, 8, #HF0

Allmem?

Header on off

Header?

Logo?

Viewangle

Options?

Viewangle?

Viewangle

Clockfreq

Clockfreq?

Clockmemory?

Clockmemory? m

Clockmemory m, f

Clocksource intext

Clocksource?

Clockstep?

Clockstep

Clockstpup and clockstpdn

Clockstpup v and clockstpdn

Savefreq m

Recallfreq m

Amplitude

Amplitude?

Clockampup and clockampdn

Clockampl

Clockampup v and clockampdn

Clockampl?

Clockoffup and clockoffdn

Clockoffset

Clockoffup v and clockoffdn

Clockoffset?

Dataampup and dataampdn

Dataampl

Dataampup v and dataampdn

Dataampl?

Dataoffup and dataoffdn

Dataoffup v and dataoffdn

Dataoffset

Dataoffset?

Offset?

Offset

Errorrate offextrate3rate4rate5rate6rate7

Errorrate?

Errorsingle

Analyzer Commands

Rescurrate?

Resbits?

Resdm?

Resdmper?

Resefs?

Reserrors?

Resefsper?

Reselapsed?

Reses?

Resesper?

Reslos?

Resphaes?

Resses?

Ressesper?

Resstart?

Resstop?

Ressync?

Restes?

Restesper?

Restotrate?

Resus?

Resusper?

Totalbits?

Totalerror?

Totalrate?

Totaltime?

Clockterm?

Clockterm neg2v gnd ac

Datadelup and datadeldn

Datadelay

Datadelay?

Datadelup v and datadeldn

Dataterm?

Dataterm neg2v gnd ac

Datathrup and datathrdn

Datathrup v and datathrdn

Datathres

Datathres?

Rdatadelup and rdatadeldn

Rdatadelup v and rdatadeldn

Rdatadelay?

Rdatadelay

Rdataterm neg2v gnd ac

Rdataterm?

Rdatathrup and rdatathrdn

Rdatathrup v and rdatathrdn

Rdatathres

Rdatathres?

Autosearch?

Autosearch auto off disab

Automode?

Automode ber, fast

Autosample?

Autosample n

Autothresh n

Autothresh?

Autowidth?

Errorreset

Dispselect total window test

Dispselect?

Histryclear

Histrybits?

Histrypower?

Histryphase?

Histryphase on

Histrystat?

Sync?

Histrysync?

Testdiscard

Testlength t

Testlength?

Testmode untimedtimedrepeat

Testmode?

Testprev currentprevious

Testreport eotonerrorbothnone

Testprev?

Testprint

Testreport?

Testsquelch onoff

Testsquelch?

Teststate?

Teststate runstop

Testthres?

Testthres

Winbitlen

Winerror?

Winbitlen?

Winbits?

Winmode?

Winmode bitssec

Winprev currentprevious

Winprev?

Winrate?

Winreport onoff

Winreport?

Winseclen s

Winseclen?

Wintime?

Printenable onoff

Printenable?

Printport parallel gpib serial

Printport?

Printstring s

Printport Parallel

Audioratup and audioratdn

Audioratup v and audioratdn

Audiorate

Audiorate?

Audiovol

Audiovol?

Audiovolup v and audiovoldn

Audiovolup and audiovoldn

Date?

Date yyyy-mm-dd

Time?

Time s

MB Option Commands

Byteblock a, i, b1, ..., bn

Byteblock? a

Bytedelete a

Byteedit? a

Byteedit a, b1

Byteinsert a, i, b1, ..., bn

Bytefill i, b1, b2, ..., bn

Bytelength?

Bytelength m, n

Bytemode?

Bytemode n

Bytesync n Analyzer only

Ratio errors/bits

Bytesync? Analyzer only

Level

Editbegin n

Editend n

Editcntrl?

102

Gpib Interface Device Settings

Using the Gpib Interface

Gpib Connector Pin-Outs

Programming Gpib Remote Commands

Interface Functions

Gpib Numeric Responses

Gpib Status Reporting

Status Byte

Service Request Enable

Service Request SRQ

Standard Event Status Register

Standard Event Status Enable Register

Test Status Event Enable Register Analyzer only

Test Status Event Register Analyzer only

Additional SRQ Gpib Commands Rx only

Gpib Common Commands

Power-on settings

IEEE-488.2 Programming Manual Requirements

Overlapped vs. Sequential Commands

Specific Command Implementations

Functional Elements

Self Test Query

RS-232 Interface Device Settings

Using the RS-232 Interface Option

RS-232 Interface Hardware/ Handshaking Considerations

RS-232 Interface Testing

Programming RS-232C Remote Commands

RS-232C Error Messages

Using GPIB, RS-232

Customer Acceptance Test For GB1400 Generator & Analyzer

Performance Verification

Functional Test

Setup for Functional Test of Standard Instrument

Confirmation of Frequency Function

Confirmation of Generator Output Data Level Change

Confirmation of Error Injection Rates

Confirmation of Selectable Analyzer Terminations

Performance Verification

Confirmation of Buttons and Indicators

Panel Lock On OFF Addr

How to Recall Factory Default Settings

Returning to Factory Default Settings

Using Front Panel Controls

Via Remote Control

Generator TX Factory Default Settings

Data Pattern

CLOCK/ Data Outputs

EOI/LF

Remote Interfaces

CR/LF

Misc

Analyzer RX Factory Default Settings

Error Beeper

Auto Search/Pattern Synchronization

Printer

Time and Date

Current BER

Test Parameters

Misc

Cleaning the Exterior

Cleaning the CRT

Cleaning the Interior

Cleaning Instructions

Pattern Editor Requirements and Features

What is MLPE?

Before You Begin

Minimum Requirements

List of Features

List of Files on this Disk

If you are using an alternate shell, such as Norton Desktop

RS-232 Cabling

Page

Page

Read Before Opening Sealed Wrapper

Pattern Editing Software

Pattern Editing Software

Pattern Editing Software

Design Overview

PLL Clock Source PCB

Data Generator PCB

Data and Clock Output Amplifier PCB

Input Amplifier PCB

GB1400 Analyzer RX

Error Counter PCB

Common to both GB1400 TX and GB1400 RX

Front Panel PCB

GB1400 Tx

Figure I-2. Block Diagram GB1400 RX

Glossary/ Index

Address

Bit Error

Analog-to-Digital Converter

Attenuation

Bit Rate

Error Detection

Byte

Channel

Multi-Channel Cable

Residual error rate

Noise

RS-232C

Glossary-4

Appendices

Auto Search

Figures

Index-3

Tables